The thing that nobody really wants to admit, even within the cohort, is that being an ETA can be an intensely lonely experience. It’s a natural part of the ETA job – you cannot feel lonely if you do not feel invested, and some degree of emotional investment is definitely required in order to be an ETA. So this loneliness is the other side to the emotional rewards. It’s the shadow that lurks behind every luminescent moment. It’s the silent story behind every beautiful/funny/inspiring photo posted to Facebook. It’s the secret that you learn to keep, because you do not want to appear ungrateful, or unsuccessful, or poorly adjusted.

But the fact remains. You are an outsider.

You are an outsider when you arrive, new and clueless, in your placement.

You are an outsider, speaking too loudly and in the wrong language.

You are an outsider with strange hair/eyes/skin/height/weight.

Sometimes, you are an undercover outsider, because you look like an insider, but in your heart, you know who you really are.

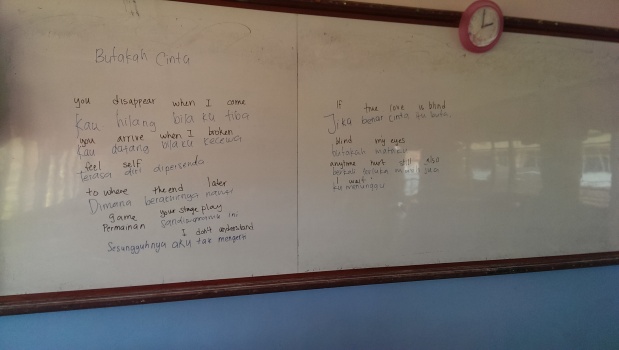

Sweating profusely, you pose a question to a packed classroom, only to have the students answer with uncomprehending silence and averted gazes. In the canteen, you listen passively to the teachers’ gossip in BM, only catching every tenth or twentieth word; when you ask for elaboration, they glance at each other and giggle, then wave your question away.

There are days when assembly runs late and you sit alone in the teachers’ room, wondering where everyone is. Days when you rush to class, only to encounter an empty room; all of the students are attending a special lecture in the hall, and you’re the only one who wasn’t told. Days when all of the teachers are resplendent in their matching school batik, and you stick out like the ugly duckling because you wore your ill-fitting secondhand baju kurung as usual. Days when someone brings a batch of scarves to school and all of the teachers gather around, chattering merrily and posing as they try on their new hijab, while you sit at the other end of the room and watch them wistfully.

You’re under constant scrutiny. Every eye is always upon you, taking in what you are wearing that day, how much you are sweating, how many pimples have erupted on your forehead, how dark the shadows under your eyes are, what you eat (or don’t eat) for lunch, how much you smile (or don’t), how you shape syllables in Bahasa Melayu with your clumsy foreigner’s tongue.

Each moment is like a tiny grain of sand, chafing against your skin. Individually, they can be tolerated, even ignored. But eventually, all of those small, rough moments begin to add up, their effects compounding until you feel raw and ready to scream. It elicits too many adolescent memories of sitting alone and feeling tears prickle at the backs of your eyes because you feel ignored, inadequate, excluded.

And the worst part: these moments never really stop, not even in the second year. Maybe they happen less frequently. Maybe you develop a tougher skin, a callus over your heart to prevent it from breaking. Maybe you learn new methods of avoidance, of negotiation, of resistance.

But in the end, it still happens. And sometimes, the moments are not grains of sand that you can brush off and disregard. They are large stones, that fly out of nowhere to hit you straight in the chest, so that you find yourself sitting on the ground, winded and nauseated, wondering what the hell just happened to you. These are the moments that demand your attention with their insistent weight, reminding you that you will always be outside, always other.

You sign on to help with the track and field team. You shove your sweaty, uncooperative body into a skin-tight sateen wedding dress and allow students to take a shot at contouring your face and shading your “Miss, so small” eyes. You spend two hours in the blazing hot afternoon parading around the open field, and help the team to win second place in the mascot competition.

On the last day of the tournament, all teachers involved with the track team show up wearing matching red polos, with the words TEAM SMKSM printed across the shoulders. You wear your normal baju kurung uniform. When your head of co-curriculum shows up, wearing the same polo as everyone else, he looks at you in surprise. “Why you not wear red T-shirt?”

“Because I didn’t get one,” you say. “Nobody told me.” The words come out sharper than you intended. The head of co-curriculum looks embarrassed; whether it’s for himself, or for you, you’re not completely sure. You turn away. You can’t bring yourself to care.

You’re invited to attend a prefect camp with your students. You’re excited to go – it’s an overnight camp, and you’ve been promised a space in the girls’ dormitories. You’ve always wished that there was a hostel at your school, so that you could spend all day with the students you love so much. You imagine staying up late into the night with your students, trading gossip and hoarded snacks, letting them giggle and whisper scandalous stories into your ear. Two days before you’re scheduled to leave, one of the English teachers, your friend, comes to you with a tight look on her face.

“Maybe it’s best if you don’t stay overnight,” she says. Her eyes are focused somewhere around the vicinity of your eyebrows, avoiding your actual gaze. “The other teachers…they don’t think it will be good for you to stay in the dorms.”

It takes a long time for you to understand what she’s saying. Her English isn’t the problem, never has been; it’s the way that she circles around the subject that confuses you. This teacher has always been straight with you. You sense that she is the bearer of some bad news, and is trying to soften the blow by delivering it in a roundabout fashion. You wish she wouldn’t do that – she means well, but this beating around the bush is just making you more nervous.

Finally, it comes out. The other female teachers do not want you to stay overnight in the dormitories, because they do not want to share a room with you. You say that you can stay with the students, but the teacher shakes her head and tells you that there’s no space. You ask – demand, really – why you can’t stay with the teachers.

The words come out haltingly. “Because…some of the teachers – the older teachers, actually – are very…traditional. They are…not comfortable with…with sharing a room…with you. They think…they think that, even though you are also a woman…” She takes a deep breath. For the first time during this uncomfortable exchange, she actually looks angry, though you sense that it’s not directed at you. “Even though you are a woman, because you are not Muslim, you are basically like a man, for them. They cannot take off their scarves in front of you.”

You have no reply. The teacher rushes to reassure you. “I tried to change their minds. I told them, she’s not going to reveal any of your secrets.” What secrets, you wonder distantly – that they have actual hair underneath their hijab? “But it’s very difficult to convince them. They are old and they do not want to change. But I don’t agree with them. If I was going, you could share a room with me.”

But the fact of the matter is, she isn’t going. The other teachers do not want you in their living space. Your head whirls with feelings of disappointment and frustration, but in the end, all you can say is, “Okay.”

It’s common practice to cook a large batch of food and bring it to the teachers’ room for everyone to share. You love to cook, so you make plans to try your hand at cooking Malay food sometime. Nasi lemak, perhaps – they’d probably get a kick out of that. But your mentor tells you, in an indirect way, that perhaps that’s not such a good idea. “Simple things are okay,” she says. “Or things that you make with the students. But other things…you know, the teachers will ask many annoying questions about the ingredients. They will tell students not to eat it. They will keep bothering you. So maybe it’s better not to do it.”

You hear the unspoken message: they are worried that your food is not halal. Somehow, this wounds you even more deeply than the incident with the overnight camp. You live in a majority Muslim community. Your landlord is Muslim, and you have kept the house as halal as you can. You shop in the same places that all of your students and coworkers do. All of your groceries carry the “halal” stamp. All of your meat is sold by Muslim butchers. You would double-, triple-, quadruple-check that all of your ingredients were halal before beginning to cook anything.

In a community that values food, where the common greeting is “Sudah makan?” (Have you eaten?), it hurts that they do not trust you enough to accept what you make, and that they would go so far as to dissuade students, who are generally open to trying anything you offer, from eating your food. You try to argue, asking where you would even manage to get non-halal ingredients nearby, but in the end, it’s useless, because you cannot force people to eat something that they do not want to eat. In the end, you’re the one who has to step down, your heart tight as a clenched fist, and accept the inevitable.

Someone once said to you, “In Malaysia, we are all one big family.” Malaysians call their seniors “abang” or “kakak” (older brother or sister), “mak cik” or “pak cik” (aunty or uncle). They call their juniors “adik,” the non-gendered term for younger sibling.

In your first year, you allow an entire Form 5 class to call you Kak instead of Miss. You’ve been an older sister, both blood and surrogate, for most of your life, so it comes easily to you, more easily than being a teacher does. You have a few other female students who ask, shyly, whether they can call you sis. Eager to be accepted, you say yes. Yes, yes, yes. And these relationships often turn out to be the closest and most fruitful ones in your entire experience.

But there are moments that remind you that there are parts of students’ lives that you will never know, no matter how much they call you kakak and shower love upon you.

In your first year, you hear that one Form 4 student – the head prefect, no less – has punched another prefect in the face. You see the cut and swollen cheekbone on one boy, the bandaged, bruised knuckles on the other. You hear, secondhand, about the punishment that might be meted out. The head prefect will definitely be stripped of his prefect status. He might be expelled. If he isn’t expelled, his parents will probably transfer him to another school. The boy who was punched does transfer. You talk to other students and they nod knowingly. “Well, why would we want to stay in the same school as someone who punched us?” one asks you rhetorically.

The entire thing just about shatters your heart. You had worked with these two boys closely as part of the English drama team. You thought you knew them. One demanded attention with his loud voice and flamboyant antics, but was always a stellar leader where it counted; the other was like a slightly awkward, yet very responsible little old man. They always made time to talk to you – one flirted outrageously with you, just to make you laugh, while the other wrote long paragraphs in his dialogue notebook, asking you to come meet his parents sometime. You liked them both.

Now, you don’t know what to think. Now, you’ve caught a glimpse of the ugly parts of their personalities, the parts that they tried so hard to keep hidden from you. And the fact that you didn’t catch this before, that you didn’t sense the violence and the vulgarity that lay just behind their smiling faces, makes you feel like there was always a wall there, invisible to your eyes, but solid and immutable all the same.

This is what drags you down when you feel like you should be flying. This is how burnout begins. This is what causes you to withdraw, curling in to protect the soft, vulnerable parts of yourself. This is how you begin to miss home, longing to be in in a place where your presence is never questioned, never even remarked upon.

So then, what’s the point?

At the water break meeting, the ETAs talk a lot about discomfort, about not fitting in, about moments when the puzzle pieces don’t line up. The mood is a little bit bleak. The director of MACEE, who has seen cohort after cohort of ETAs come and go, reminds everyone that discomfort is an underrated feeling, and it’s in those moments of prolonged discomfort that true growth can happen. Nothing really happens when everything is comfortable and perfect. Discomfort is a catalyst, a galvanizer.

Loneliness can be terrible, and in the worst cases, it can be crushing. It lives in the mind, so it is difficult to hide from, and impossible to kill. So to defeat it, you must make peace with it. When it does arise, let it wash over you. Recognize that loneliness is like a tide – at some point, it must recede. It may not recede quickly, and it will never recede completely, but it must recede all the same.

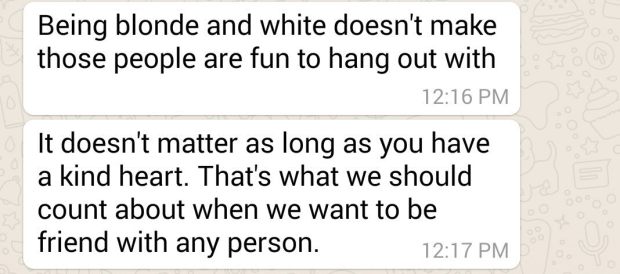

And being an outsider, an other, is not the end of the world. Being an outsider in this new environment should remind you that, back at home, there are also outsiders. Sometimes they are invisible, and sometimes they are persecuted. At times, you may have been one of them. So at the end of the day, you learn sympathy for those who must always exist somewhere outside. You learn how to reach across the boundaries, to grasp for connections when other people have given up, because you know how it feels to be left out. You learn how to listen to the story beyond the surface. You learn the value of every small gesture that strives towards inclusivity. You learn how to become more kind, more empathetic, and more complete.